SWPM has been recognized as a major pathway for introduction of tree-killing pests since the Asian longhorned beetle was detected in New York and Chicago in late 1990s. As of 2014, 58 new species of non-native wood- or bark-boring insects had been detected – many probably introduced via wood packaging [Leung et al. 2014]. Other examples include the emerald ash borer, redbay ambrosia beetle, and, possibly, the invasive shot hole borers.

In response to recognition of the pest risk associated with wood packaging, countries adopted ISPM#15. This process was reviewed in the two articles by Haack et al. and my recent blog. I provided the broader context of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in my Fading Forests II report.

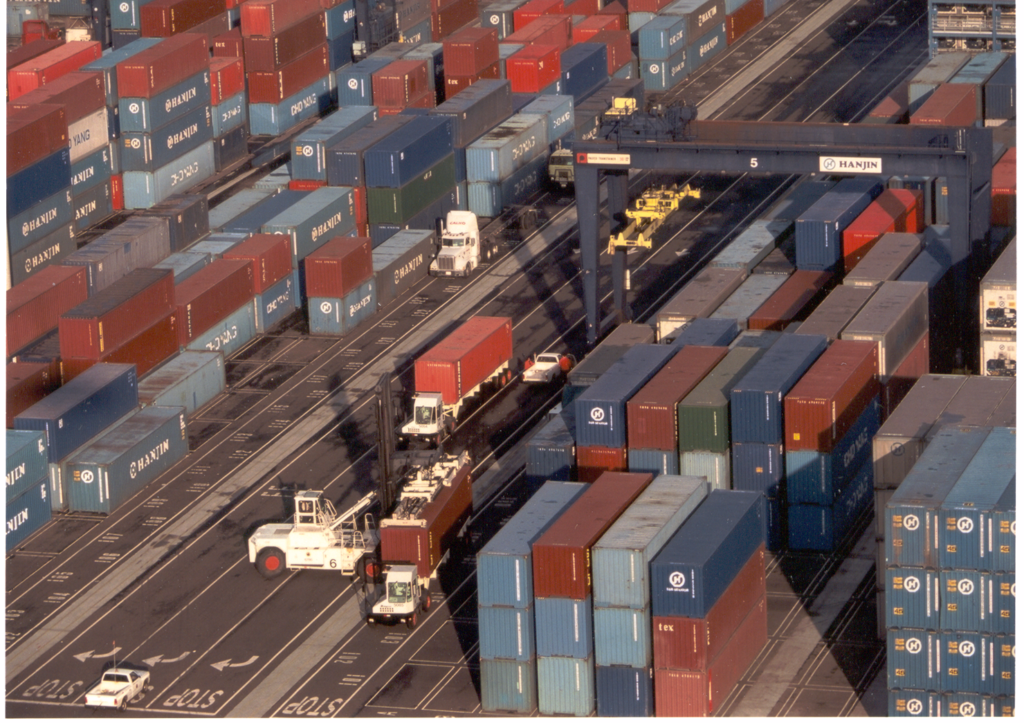

I have blogged often about the continuing poor compliance with wood packaging regulations, especially by China; and USDA APHIS’ insufficient efforts to fix the problems. The DHS Bureau of Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has tried much harder. See particularly my blog about Bob Haack’s re-evaluation of the pest approach risk in wood packaging. Given the high volumes of imports, pests infesting even a small proportion of incoming shipments can result in tens of thousands of pest-infested containers entering the U.S. or Canada each year. For an explanation of these calculations, see the “background” section of this blog.

Since 2010, CBP has discovered actionable pests in more than 700 shipments each year (pers. comm.). [APHIS reports half as many detections – 300 wood boring and bark beetles (Greenwood et al. citing APHIS report from 2021). Perhaps the difference arises from some of the actionable pests not being wood-borers, e.g., snails.] The persistence of pest presence has disappointed CBP staffers, because the agency has taken several actions intended to discourage violations. These include imposing fines and revoking the violators’ participation in the U.S. Trade Partnership Against Terrorism (C-TPAT) program. Greenwood et al. describe these consequences of non-compliance, as well as the expense of re-exporting the goods and associated wood packaging, as “significant”. Regardless of how significant they might be, so far these consequences have not reduced non-compliances substantially.

The fact is, countries cannot rely on the presence of the ISPM#15 mark or stamp to indicate that the wood packaging is pest-free. In both the United States and Europe, more than 90% of the SWPM found to be infested has born the ISPM#15 stamp (pers. comm.; Eyre et al. 2018). All the pest-infected shipments imported after 2006 discussed in the Haack et al. 2022 study were in wood packaging bearing the ISPM#15 mark. While many of the problems arise on shipments from Asia, findings occur sporadically with countries all across the globe- and notably, U.S. importers have also found serious problems with dunnage from Europe.

But that is the purpose of the standard!

Two outstanding questions that need answers

- Continuing poor compliance with regulations by China. This is despite the fact that the U.S. and Canada have required treatment of wood packaging from China since December 1998 – nearly 24 years. Haack et al. found that the proportion of Chinese consignments with infested wood is five times greater than expected based on their proportion of the dataset. The rate of wood packaging from China that is infested has remained relatively steady: the Chinese infestation rate was 1.26% during 2003–2004, and ranged from 0.58 to 1.11% during the next three periods.

Why are the responsible agencies in the United States not taking more aggressive action to correct this long-standing problem? This is a matter of political will.

- Despite the ISPM#15 mark being unreliable for more than a decade, countries have not carried out research to determine the root causes. Even now (i.e., Haack et al. 2022; Greenwood et al.) no one can say what proportion of these ISPM-marked but pest-infested pieces of wood results from the treatment not being effective in killing all pests; what proportion results from inadequate application of treatments that are per se effective; and what proportion from fraud (deliberate claims to have applied a treatment that was not done)?

Admittedly, answering these questions will not be easy. First, there is no independent test for whether treatments have been applied; the treatments do not alter the wood’s properties in measurable ways. Scientists need experiments to test the real-world efficacy of treatments in the specific contexts of solid wood packaging.

Second, each country is responsible for its own compliance. Countries differ in their capacity and political will to address this issue. However, success of ISPM#15 depends on determining the cause of continuing pest presence in wood marked as treated, and taking appropriate action to solve the underlying problem.

Greenwood et al. attempt to make progress toward carrying out this necessary task by describing the many steps in the wood packaging supply chain, associated opportunities for pests to infest the wood at each step, and actions exporters and importers can take to try to minimize the risk.

Again, as I discussed in the earlier blog, Haack et al. (2022) found several disturbing situations:

- While the pest approach rate has fallen since U.S. implementation of ISPM#15, the extent of the decline has progressively decreased as time passes. The reduction during 2005–2006 was 61%; during 2007–2009, 47%; during 2010-2020 only 36%.

- The 2010 – 2020 pest approach rate was calculated at 0.22%. This is more than double the rate based on 2009 data (0.1%, as stated in Haack et al. 2014). While we cannot directly compare these two data points (the two studies used different methods, as discussed in the blog), the bottom line is that the approach rate remains too high. Our forests continue to be exposed to the risk of introduction of highly damaging wood-boring pests. Furthermore, since the number of countries sending us infested wood packaging has increased, those potential pests include insects from a greater variety of countries (biomes).

- The two most commonly intercepted families of wood borers are Cerambycidae and Scolytinae (Haack et al. 2022). These families include the Asian longhorned beetle, , redbay ambrosia beetle, and invasive shot hole borers. The 2009 amendment requiring debarking has not apparently resulted in substantial decreases in pest presence, although the proportion of pests that are true bark beetles has declined – from 100% of Scolytinae identified to genus or species detected before 2009 to only 23% in 2010–2020 period.

Haack et al. (2022) Recommendations

Haack et al. (2022) call for several improvements. Several pertain to how data are collected. Recording the number of infested pieces of wood instead of reporting only consignments would help clarify whether the numbers of insects reaching our borders has fallen, risen, or remained steady. Recording the presence of bark – and the size of any bark remnants – would help clarify whether pests are re-infesting treated wood.

They also note opportunities to improve ISPM#15 implementation and enforcement through training. However, compliance issues persist despite past educational efforts by APHIS and the IPPC.

The Wood Packaging Supply Chain Offers many Opportunities for Pests to Infest the Wood

Greenwood et al. describe each step in fabricating wood packaging material and the opportunities each step presents for unwanted organisms to enter that supply chain. They note that ensuring that these organisms are not then transported on wood packaging being used to carry goods requires that the pests be removed; rendered infertile, inactive, unable to complete development or reproduce; or killed.

The first step in fabricating wood packaging is to harvest trees. Those trees probably harbor various insects, fungi, nematodes, and other organisms that use trees as a resource — for food, shelter, or as a substrate for oviposition. Greenwood et al. mention that the multiplicity of organisms’ life histories pose different challenges for detection and management depending on size, type of tissue utilized, and other factors. The likelihood that a pest or pathogen will be present on or in tree tissues depends on several biotic and abiotic factors, including a species’ proclivity to experience periodic or episodic outbreaks; blow-down events (e.g., hurricanes, windstorms); and harvesting practices. Some of these factors can be controlled by people harvesting the wood.

One of the most frequent opportunities for pest infestation, escape, or cross-contamination is when the wood is stored in the environment. Such storage events happen after the tree is felled — at either the harvest site or processing facility; after the pallet or crate is built – either empty or after the goods have been packed; at the port of export before embarkation; at the importing port before inspection or onward transport; at distribution centers; at retailers; at “pallet graveyards” while awaiting repair or recycling. Retailers and customers have few resources for responsible handling of SWPM – and few incentives to be careful.

The risk is exacerbated if storage takes place near woodlands. photo from Savannah At ports and distribution centers, the presence of SWPM from many origins adds to the risk of cross-contamination. Enclosing the SWPM in containers does not completely eliminate the risk since organisms might enter through cracks or air vents. Greenwood et al. suggest management tactics to prevent or reduce pest interaction with the wood during these periods.

One of the ISPM#15 requirements intended to minimize the pest risk is debarking the wood. This process removes most organisms that live in and just under the bark. However, debarked wood usually retains some patches of bark because trees are not perfectly round cylinders. Therefore ISPM#15 specifies that remaining bark must be less than 3 cm wide or, if the piece is longer than 3 cm, less than 50 cm2 in area.

Greenwood et al. state that after debarking and treatments per ISPM#15, the risk that a pest will be present on the SWPM has been significantly reduced. However, other challenges appear as the newly-minted packaging is put into use – primarily through the possibility of contamination during storage – as described above. There are also risks associated with inadequate or insufficient treatment or fraud.

Once loaded onto a ship, containers and any SWPM, including dunnage, are very difficult to inspect. That means that the loading process presents that last opportunity for inspection and mitigation of contaminating pests. Greenwood et al. note that it is the shipper’s responsibility to ensure containers are “clean, free of cargo residues, noxious materials, plants, plant products and visible pests” before being loaded on the ship. However, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) provides only recommendations, not mandates. Australia has adopted more stringent requirements.

Arrival at the importing country’s port presents the first opportunity for non-indigenous organisms to escape and the first domestic opportunity for the receiving country to inspect the shipment. While U.S. and Canadian customs agencies have authority to board ships before they dock to inspect them, Mexican agencies do not. The most extensive pre-docking requirements are aimed at preventing arrival of moths in the Lymantria genus from Asia.

Greenwood et al. note that dunnage presents unique risks. After it is removed from ships during the unloading process it is often stored at the port. As noted above, storage in the open allows pests to escape to nearby trees or to cross-contaminate other SWPM. Ports struggle to manage these piles. In 2016 the U.S. revised its regulations to allow for the more rapid destruction of illegally deposited dunnage via incineration at the port. Since 2008 Canada has considered all shipborne dunnage to be non-compliant – regardless of whether it bears the ISPM#15 stamp. In the largest Mexican ports, dunnage is fumigated and destroyed. However, the dunnage might be stored in the open for considerable periods before being destroyed.

Worse, it is often impossible to assign chain of custody information and responsibility for either disposition of non-compliant dunnage or penalties for non-compliance. Dunnage or blocking pieces might be added immediately before shipping by entities other than the owners or brokers for the commodities being shipped. I have already noted that it is nearly impossible to inspect dunnage in a ship’s hold.

Unfortunately, studies have not clarified the level of infestation of dunnage in comparison to other wood packaging types made from multiple pieces of milled wood, such as pallets or spools.

Greenwood et al. describe the different fates of pallets, dunnage, crates, spools, and other types of SWPM. Wood pallets are frequently recycled or remanufactured in the U.S., although there are no data on the proportion of the recovery market that is composed of pallets initially manufactured overseas. In the U.S., most repairs are done with components from reclaimed pallets so they probably conform to ISPM#15 repair guidelines. However, contamination could happen while the pallets are in storage awaiting reuse. As SWPM ages, different types of pests might be attracted.

SWPM deemed not suitable for reuse is either destroyed in controlled settings (i.e., solid waste facilities, wood processing facilities, or landfills), used in recycling or downcycling markets, or reclaimed. It might be chipped and sold as mulch, soil amendment, or animal bedding; or it might enter the commercial fiber market and be manufactured into other wood products (e.g., paper, chipboard, fuel pellets). These dispositions present very low pest risk, due to the final dimensions of the wood products being too small to sustain pest development in most cases. However, some microorganisms and very minute arthropods might persist even on chipped or shredded material. There is little data on the final disposition of SWPM globally.

Greenwood et al. reiterate that the presence of hitchhiking or contaminating pests does not imply failure of ISPM#15 treatments, which do not target such organisms. Such pests can also be present on non-wood packaging material such as plastic and metal. Countries vary in their concern about these hitchhiking pests, which include dry wood borers and brown marmorated stinkbug (Halyomorpha halys). Since these pests are not addressed by ISPM#15, countries can implement their own management strategies to counter contaminating pests on all SWPM, containers, and conveyances. Indeed, Pennsylvania regulates the movement of SWPM and other high risk articles to prevent the spread of the non-specific hitchhiking pest, spotted lanternfly, Lycorma delicatula.

They also note that reuse, disposal, and recycling of packaging made from metal, plastic, or even paper requires very different processes and facilities than those used for wood.

Greenwood Recommendations

Greenwood et al. advocate additional research on several questions:

- to test whether currently accepted ISPM#15 treatments are sufficiently effective within the newly proposed metrics found in Ormsby 2022.

- to determine the risk profile and enforcement of dunnage, especially whether organisms in dunnage are more likely to survive treatment (dunnage pieces are often much larger than any component piece of a pallet or crate).

- to develop new treatments – including to counter re-infestation later in the supply chain. Scientists will probably have to replace Probit9 as a standard because it is not practical to exposing tens of thousands of wood-infesting insects to the new treatment. This is also discussed in Ormsby 2022.

- to develop ways to test whether treatments have been applied – needed to verify whether fraud has occurred.

- social and economic motivations around compliance

Most of these studies will require international cooperation.

Other steps are also need. As U.S. importers of break-bulk cargo have found out, procuring apparently compliant SWPM does not protect them from legal, financial, and logistical consequences if that SWPM turns out to be non-compliant or otherwise infested with live actionable pests. Some importers have begun exploring options toward additional private inspection at the exporting port, beyond solely requiring the use of ISPM#15 compliant materials. Greenwood et al. suggest the possibility of third-party certification. They also supported calls for officials to release of information about which foreign facilities have a history of selling SWPM subsequently found to be non-compliant. This information would empower importers to procure pest-free SWPM – thus harnessing market incentives to improve compliance.

Greenwood et al. say that reducing external contamination on conveyances – ships, airplanes, trucks, and trains – is challenging. It would require the cooperation of multiple entities who manage yards, equipment, and facilities. Improved management must make sense to people who have severe constraints on time, staffing, space, and safety protocols. Persuading them to act will probably depend on improved information (research) on the cost effectiveness of various strategies and real-world incidence of contamination in different storage scenarios (beyond Lymantria complex), plus development of new surveillance tools.

Greenwood et al. suggest that conducting a HACCP assessment of the supply chain could help identify how a systems approach might better mitigate pest risks of SWPM. They think systems approaches might be especially promising for reducing risks of contaminating organisms. NAPPO recently adopted a standard for designing and implementing systems approaches for wood commodities.

Finally, I remind you of my recommendations for immediate policy actions to hold foreign suppliers responsible for non-compliant wood packaging:

- U.S. and Canada should refuse to accept wood packaging from foreign suppliers that have a record of repeated violations – whatever the apparent cause of the non-compliance. They should institute severe penalties to deter foreign suppliers from taking devious steps to escape being associated with their violation record.

- I also support the suggestion (above) that phytosanitary agencies inform importers on which foreign treatment facilities have a record of poor compliance or suspected fraud – so the importers can avoid purchasing SWPM from them.

- U.S. and Canada should encourage importers to switch to materials that won’t transport wood-borers. Cardboard and manufactured wood packaging (e.g. oriented strand board and compressed wood block) are wood fiber products that have near zero risk of wood-borer infestation. Plastic is also one such material. I note that Earth is drowning under discarded plastic.

APHIS and CFIA have the authority to take these action under the “emergency action” provision (Sec. 5.7) of the World Trade Organization’s Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Standards (WTO SPS Agreement). (For a discussion of the SPS Agreement, go to Fading Forests II, here.)

Longer-term Actions

APHIS and CFIA should exercise their right to set a higher “level of protection” to minimize introductions of pest that threaten our forests (described inter alia here.) They should prepare a risk assessment to justify adopting more restrictive regulations that would prohibit use of packaging made from solid wood – at least from the countries with records of high levels of non-compliance.

The studies needed to determine the cause of the continuing issue of the wood treatment mark’s unreliability, and appropriate actions to fix the problem, should be conducted with other countries. Appropriate entities would be the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC) and International Forest Quarantine Research Group (IFQRG). However, if attempting such collaboration causes delays, APHIS and CFIA should begin unilaterally.

Meanwhile, what can we do?

- Urge Congress to conduct oversight on APHIS’ failure to protect America’s natural resources from continuing introductions of nonnative insects and diseases. Note that the Mediterranean oak borer has apparently been introduced several times in recent years – despite ISPM#15.

- Raise the issue with local, state, and federal candidates for office;

- Urge Congress to include provisions of H.R. 3174 / S. 1238 in the 2023 Farm Bill;

- Ask any associations of which you are a member to join in communicating these concerns to Congressional representatives and senators. These include:

- if you work for a federal or state agency – raise to leadership; they can act directly or through National Plant Board, National Association of State Departments of Agriculture, National Association of State Foresters, National Governors Association, National Association of Counties …

- scientific membership societies – e.g., Society of American Foresters, Entomological Society of America, Phytopathological Society;

- individual conservation organizations, either with state chapters or at the national level;

- woodland owners’ organizations, e.g., National Woodland Owners Association, National Alliance of Forest Owners, and their state chapters

- urban tree advocates

- International Forest Quarantine Research Group

- Write letters to the editors of your local newspaper or TV news station.

SOURCES

Eyre, D., R. Macarthur, R.A. Haack, Y. Lu, and H. Krehan. 2018. Variation in Inspection Efficacy by Member States of Wood Packaging Material Entering the European Union. Journal of Economic Entomology, XX(X), 2018, 1–9 doi: 10.1093/jee/tox357

Greenwood, L.F., D.R. Coyle, M.E. Guerrero, G. Hernández, C.J. K. MacQuarrie, O. Trejo, M.K. Noseworthy. 2023. Exploring pest mitigation research and management associated with the global wood packaging supply chain: What and where are the weak links? Biol Invasions https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-023-03058-8

Haack, R.A., K.O. Britton, E.G. Brockerhoff, J.F. Cavey, L.J. Garrett, et al. 2014. Effectiveness of the International Phytosanitary Standard ISPM No. 15 on Reducing Wood Borer Infestation Rates in Wood Packaging Material Entering the United States. PLoS ONE 9(5): e96611. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096611

Haack R.A., J.A. Hardin, B.P. Caton and T.R. Petrice. 2022. Wood borer detection rates on wood packaging materials entering the United States during different phases of ISPM#15 implementation and regulatory changes. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change 5:1069117. doi: 10.3389/ffgc.2022.1069117

Leung, B., M.R. Springborn, J.A. Turner, and E.G. Brockerhoff. 2014. Pathway-level risk analysis: the net present value of an invasive species policy in the US. Front Ecol Environ. 2014. doi:10.1890/130311

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm

or