The Eastern deciduous forest is large and important ecologically. The forest is important for biological diversity: it shelters many endangered species, especially plants, molluscs and fish, mammals, and reptiles. In addition, the majority of forest carbon stocks in the U.S. are those of the eastern states.

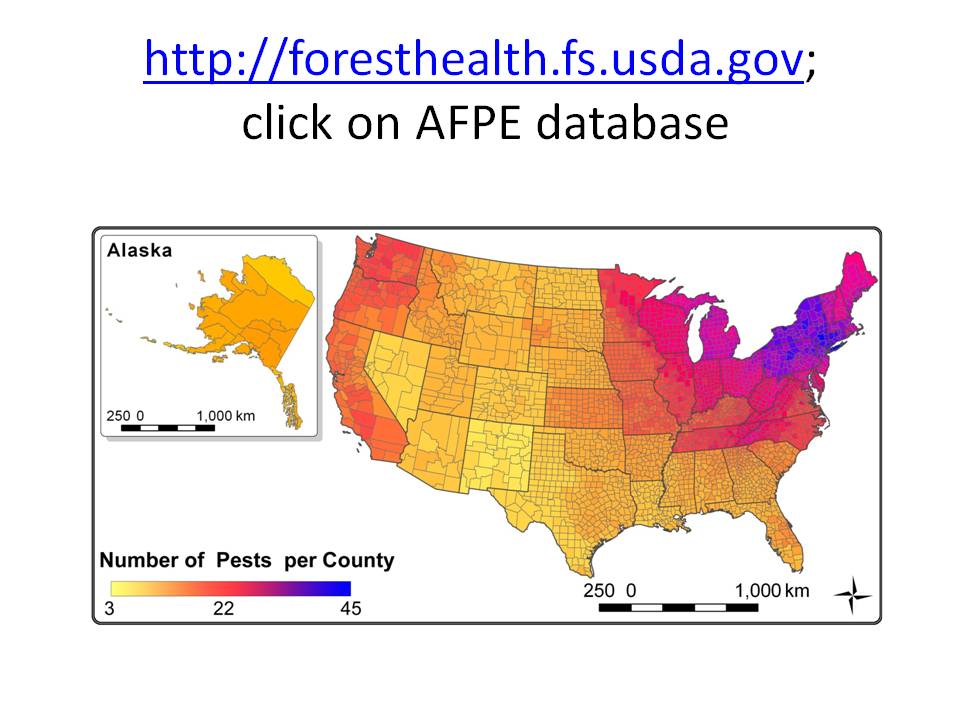

But the Eastern deciduous forest is also under many anthropogenic stresses – including high numbers of non-native insects and pathogens, Liebhold map high numbers of invasive plants, blog invasive earthworms, blog browsing by overabundant deer, and timber extraction. In the southern portions of the forest, human populations are expanding, resulting in landscape fragmentation (USDA FS 2023b RPA, full reference at end of this blog).

Agency and academic scientists in the USDA Forest Service Eastern Region (Maine to Minnesota; Delaware to West Virginia, then north of the Ohio River to Missouri) are trying to understand how long-term, continuous stressors, like deer browsing and invasive plants and earthworms, – interact with short-term gap-forming events. They call the long-term stressors “press” disturbances to distinguish them from the short-term “pulse” disturbances (Reed, Bronson, et al.; full citation at end of this blog). Understanding the processes by which forests recover from disturbance is increasingly important. Climate change is expected to raise the frequency and intensity of catastrophic natural disturbances (Spicer and Reed, Royo et al.).

The scientists emphasize that the impacts of these stressors – and effective solutions — vary depending on context.

Invasive Earthworms

USDA APHIS is responsible for regulating introduction of new species. For earthworms, APHIS’ principal concern is clearly the possibility that imported worms or soil might transport pathogens. However, the agency’s website does mention worms’ ability to disrupt the soil and possibly cause undesirable impacts on plant growth and diversity. At the 2023 National Plant Board meeting in early August 2023, Gregg Goodman, Senior Agriculturalist in APHIS PPQ NPB website for agenda? discussed issues that he considers when evaluating whether to grant permits for importing earthworms. APHIS allows imports to be used for fish bait. Dr. Goodman explained that APHIS surveyed fishermen to determine where they dump unused bait. He found no damage to plants along streams, etc. where they are dumped. A state plant health official from a northern state and I objected that the ecosystem damage caused by earthworms is well documented and we doubted that dumping of bait is not a pathway for introducing worms into natural areas.

Reed, Bronson et al. found lower earthworm biomass and density in both deer exclosures and canopy gaps. They hypothesize that the new plant growth associated with canopy gaps attracts deer, resulting in increased browse pressure. That browse pressure then affects the plant community, succession and forest structure. The changed plant community affects soil properties that then affect soil-dwelling fauna like earthworms. They believe the higher worm densities in closed-canopy sites might be the result of nutrient-rich tree leaf litter which provides both shelter and food. Another factor might be lack of recent soil disturbances in closed canopy sites.

While they say need more research is needed on the complex, combined effects of earthworms and deer, Reed, Bronson et al. still suggest that reducing deer populations or – where that is not possible – creating gaps might help manage earthworm invasions.

Deer Interactions

The long-term, chronic effect of excessive deer herbivory are well documented. See the many presentations at the recent Northern Hardwood research forum (USDA FS 2023b Proceedings). Most studies show that deer browsing overwhelms other disturbances, such as fire and canopy gaps that typically promote seedling diversity. However, recent results refine our understanding.

Samuel P. Reed and colleagues (Reed, Royo et al.) found that on the Allegheny Plateau of western Pennsylvania high deer densities at the time of stand initiation resulted in long-term reduced tree species diversity, density, and basal area. These responses were still detectable nearly four decades later. Stands are dominated by the unpalatable black cherry (Prunus serotina). The reduced stand density and the cherries’ narrower crowns lead to less above-ground biomass and reductions in above-ground carbon stocks. These scientists recommend that managers reduce deer populations to prevent changes in forest structure with probably long-term and important ramifications for many ecosystem functions.

Hoven et al. concurred with the importance of reducing deer densities, but suggested focussing on wet sites where, in their study, deer browsing had its greatest effects. On drier sites deer browsing had no effect on the diversity of woody plant seedlings.

Spicer et al. seek particularly to maintain a heterogeneous landscape to allow coexistence of both early- and late-successional species. In the Eastern Deciduous Forest biome, herbs, shrubs, and vines comprise 93% of the species richness of vascular plants

These authors found that the impact of deer browsing diverged depending on vegetation management actions. In wind-throw gaps where the plant community was retained, deer caused a 14% decline in shrub cover. In contrast, when scientists removed the extant vegetation at the beginning of recovery, deer exclusion caused a 67% increase in shrub cover. The authors speculate that vegetation removal stimulated abundant blackberry (Rubus species) regrowth. Where they had access (in gaps lacking exclosures), deer heavily browsed young Rubus stalks that sprouted after the competing vegetation was cut down. However, when the pre-established vegetation was not removed, older Rubus thickets might have protected other herbs and shrubs from browsing. Spicer et al. did not observe any major shifts in browse-tolerant species in deer-exclusion plots.

Invasive Shrubs

Hoven et al. found that in drier forest plots, the presence of non-native shrubs reduced native seedling abundance, richness, and diversity. Instead there were more seedlings of introduced species, including Lonicera maackii, L. morrowii, Ligustrum sp., and Rosa multiflora. They are concerned that replacement by invasive honeysuckles might be particularly strong in gaps resulting from death of ash trees caused by emerald ash borer. Woodlands could become dominated introduced shrubs, reducing diversity. Consequently, they recommend removing non-native shrubs in drier forests to promote seedling numbers and diversity.

In contrast, in wetter forests basal area of non-native shrubs did not affect introduced seedling abundance. However, the shrubs’ size did promote greater proportions of Lonicera maackii and Ligustrum seedlings. They suggest this might be the outcome of either abundant seed sources or allelopathic properties of some invasive shrubs e.g., L. maackii. In such sites, seedling diversity is already limited to plants that tolerate waterlogging. A hopeful note is that one native shrub, Lindera benzoin, seems able to prevent establishment of L. maackii.

Hoven et al. do worry that death of ash trees might lead to declining transpiration rates, raising water tables, and further reducing seedling species richness and diversity.

Impact of Salvage Logging and Vegetation Removal

Spicer et al. studied how anthropogenic stressors affect succession. These scientists took advantage of tornado-caused gaps to compare interactions with deer browsing, salvage logging, and mechanical removal of the understory.

Contrary to expectations, none of these anthropogenic disturbances delayed community recovery or reduced diversity in comparison to the natural disturbance (tornado blowdown). Instead, adding either salvage logging or mechanical removal of understory vegetation substantially enhanced herbaceous species richness and shrub cover.

However, each major plant growth form responded differently. First, none of the manipulations affected species diversity or abundance of tree seedlings and saplings. Second, salvage logging in the wind-throw gaps increased species richness of herbs by 30%. Shrub abundance was doubled and cover almost tripled, but species richness did not change. Third, removing competing understory vegetation caused an increase of 23% in mean herbaceous cover. I have already discussed the impact of excluding deer.

Spicer et al. greet these increases in species richness with enthusiasm; they recommend managing to create a patchwork of combined natural and anthropogenic disturbances to promote plant diversity. However, I have some questions about which species are being promoted.

This study identified a total of 264 vascular plant species: 40 trees, 190 herbs, 15 shrubs, 17 vines, and 2 of unknown growth form. Only about half of these, 123 species, grew in portions of the mature forest not affected by either the tornado or one of the anthropogenic manipulations.

Gaps contained more plant species – as is to be expected. Natural blowdown areas where no manipulation was carried out had 49 more species than the undisturbed forest community (172 species). Blowdown sites subjected to salvage logging added another 53 species for a total of 225 species, or 102 more than the undisturbed reference forest.

A total of 17 species occurred only once in the authors’ data [= unique species]. Eight of these species grew only in the undisturbed forest. Two grew only in the tornado-impacted plots. Spicer et al. do not elaborate on whether these species are officially rare in that part of Pennsylvania – although it seems they might be. I wish Spicer et al. had addressed whether these possibly rare species might be affected by the forest management they recommend, i.e., intentionally creating a patchwork of various disturbances. An additional seven unique species were found in plots that had been subjected to an anthropogenic disturbance — either salvage logging or removal of remnant vegetation.

In tornado-disturbed sites, one native species associated with areas where vegetation was left intact is one of the gorgeous wildflowers of eastern deciduous forests: a Trillium (species not indicated). The one native plant associated with plots from which vegetation was removed was a grass (unspecified).

Spicer et al. report that the proportion of the flora composed of non-native species was very similar between the salvage-logged area (7%) and the undisturbed reference forest (5%). Half of the non-native plant species (3.5% or 9 species) are listed as invasive in Pennsylvania (the article does not list them).

Spicer et al. say these non-native species are relatively uncommon and that they pose a minimal threat. They do concede that the invasive thorny shrub barberry (Berberis thunbergii) was more common in disturbed than intact areas. [I saw plenty of barberry along forest edges in Cook State Forest, which is only 100 miles away from the study site.] I think Spicer and others are too blasé since invasive plant populations can build up quickly when seed sources are present.

Spicer et al. raise two caveats. First, their results regarding the beneficial effects of salvage logging and vegetation manipulation probably will not apply to situations in which vast areas are logged.

More pertinent to us, they warn that their results would also not apply to forest areas in which propagules have been drastically depleted. This can result from previous human land-use or repeated catastrophic disturbances, such as canopy fires. Nor would their results apply to forests that are more threatened by invasive species. They note that a widespread and dense understory of multiple non-native species can create invasional meltdowns, resulting in a lasting depauperate state. This is especially the case when invaders at higher trophic levels, such as earthworms, are part of the mix.

Other Lessons

Reed, Bronson et al. conclude that forest canopies’ responses to disturbance are too variable to be measured by a single method. Evaluating proposals for management will require multiple measures. The overwhelming recommendation of presenters at the recent northern hardwoods research symposium (USDA FS 2023a Proceedings) was to adapt more flexible management strategies to promote forest sustainability and species diversity.

Hovena et al.’s principal finding is that interactions among site wetness, non-native shrubs and the total basal area of trees in the stand had the largest impacts on the species composition of seedlings. In Ohio, site wetness and chronic stressors like deer and introduced shrubs are acting together to shift seedling communities towards fewer native species. Of these three long-term “press” stresses, the interaction between introduced shrubs and soil wetness overshadowed even the impact of deer herbivory on seedling species richness and abundance. Surprisingly, site-specific characteristics – e.g., wetness, canopy tree competition, deer herbivory and introduced shrubs – were more influential than ash mortality in shaping woody seedling communities.

SOURCES

Hoven, B.M., K.S. Knight, V.E. Peters, D.L. Gorchov. 2022. Woody seedling community responses to deer herbivory, introduced shrubs, and ash mortality depend on canopy competition and site wetness. Forest Ecology and Management 523 (2022) 120488

Reed, S.P., D.R. Bronson, J.A. Forrester, L.M. Prudent, A.M. Yang, A.M. Yantes, P.B. Reich, and L.E. Frelich. 2023. Linked disturbance in the temperate forest: Earthworms, deer, and canopy gaps. Ecology. 2023;104:e4040. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/r/ecy

Reed, S.P, A.A. Royo, A.T. Fotis, K.S. Knight, C.E. Flower, and P.S. Curtis. 2022. The long-term impacts of deer herbivory in determining temperate forest stand and canopy structural complexity. Journal of Applied Ecology. 2022; 59:812-821

Spicer, M.E., A.A. Royo, J.W. Wenzel, and W.P. Carson. 2023. Understory plant growth forms respond independently to combined natural and anthropogenic disturbances. Forest Ecology and Management 543 (2023) 12077

United States Department of Agriculture. Forest Service. 2023a. Proceedings of the First Biennial Northern Hardwood Conference 2021: Bridging Science and Management for the Future. Northern Research Station General Technical Report NRS-P-211 May 2023

United States Department of Agriculture. Forest Service. 2023b. Future of America’s Forests and Rangelands. Forest Service 2020 Resources Planning Act Assessment. GTR-WO-102. July 2023 https://www.fs.usda.gov/research/treesearch/66413

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm

or