I have been disappointed that a research symposium focused on the northern hardwood forest workshop gave little attention to non-native pests (see citation at end of this blog). A new study based in the Bartlett Experimental Forest in the White Mountains of New Hampshire is more balanced. Ducey et al. (full citation at the end of this blog) analyzed changes in the forest’s species composition and tree size over the past 80 years.

They found that trees of nearly all species are growing into larger sizes as the forest continues to age since the last widespread clearing at the end of the 19th Century. The same aging is causing a rapid decline in two shade-intolerant species – paper birch (Betula papyrifera) and aspen (Populus tremuloides and P. grandidentata) – which had grown quickly once the cleared areas were abandoned. The mid-shade -tolerant species yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis) also is declining. Together, the birch and aspen species have declined from a quarter to a third of basal area in 1931 to 10 – 12% in 2015.

Some developments are unexpected. Red maple (Acer rubrum) increased in abundance until the early 1990s, but that growth then levelled off. Sugar maple (Acer saccharum) has declined in abundance except where the forest is managed to retain it.

There is little evidence of tree species migrating upward on slopes in response to changes in the local climate. Major weather events – a hurricane in 1938 and an ice storm in 1998 — caused significant tree mortality across Bartlett Experimental Forest, but not a dramatic change in forest composition.

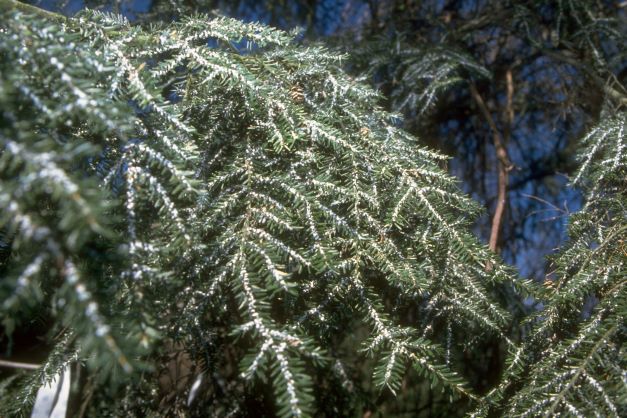

Eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) is replacing the disappearing birch and aspen on low elevation sites. Hemlock has increased its proportion of basal area from 8 – 10% to a quarter or more. Despite aggressive management aimed at reducing the tree’s presence, American beech (Fagus grandifolia) is on track to dominate large areas of the Bartlett Experimental Forest. Given the tree-killing pests already present in the region, large increases in eastern hemlock, American beech, and red spruce (Picea rubens) are worrying.

Eastern hemlock creates important wildlife habitat for deer and more than 100 other vertebrate species in New England. However, hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA) has been present in New Hampshire since 2000. It is now within 15-20 km of Bartlett Experimental Forest. There is some hope that the region’s cold temperatures might limit HWA’s spread and impacts, but Ducey et al. expect major change when the adelgid arrives.

Ducey et al. cite a separate study demonstrating that mortality caused by beech bark disease (BBD) can be sufficient to upset carbon storage in old-growth forests. On the Bartlett Forest, nearly 90% of beech trees had become diseased by 1950.

Ducey et al. express concern about the possible impact of beech leaf disease (BLD), as well.

BLD has not yet been detected in the White Mountains or New Hampshire, but is in so New England and coastal Maine. Much remains unknown about the disease, including how it spreads and its long-term impacts.

Ducey et al. do not raise pest concerns about red spruce or balsam fir (Abies balsamea), which co-dominate the Bartlett Forest at higher elevations (above 500 m). This silence is disturbing since red spruce can be killed by the brown spruce longhorned beetle, a European woodborer established in Nova Scotia and threatening to spread south. Balsam firs suffer some mortality from feeding by the balsam woolly adelgid, a Eurasian sap-sucker which has been in New England for more than a century.

White ash (Fraxinus americana) is present as a minor component of the Bartlett Forest. Because it is considered to be a valuable timber species, management has resulted in a modest increase in abundance of ash. Ducey et al. expect dramatic reduction — or even elimination of the species — when the emerald ash borer (EAB) arrives. EAB has been detected within ~ 15 km from Bartlett Experimental Forest.

Ducey et al. conclude that silvicultural management applied at the scope and intensity of that in the Bartlett Experimental Forest has moderated some changes. That is, it is maintaining sugar maple and suppressing the increase of beech. Its effect is secondary, however to overall forest development as the forest ages.

SOURCES

Ducey, M.J, O.L., Yamasaki, M. Belair, E.P., Leak, W.B. 2023. Eight decades of compositional change in a managed northern hardwood landscape. Forest Ecosystems 10 (2023) 100121

Proceedings of the First Biennial Northern Hardwood Conference 2021: Bridging Science and Management for the Future. USDA Forest Service Northern Research Station General Technical Report NRS-P-211, May 2023

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm

or