Those of us striving to increase action! to curb bioinvasion have had a hard time demonstrating socio-economic costs sufficiently compelling to prompt adoption of more effective policies. However, see

- Donovan, et al. 2013. The Relationship Between Trees and Human Health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. Volume 44 Issue 2.

- Fantle-Lepczyk, et al. 2022. Economic costs of biological invasions in the United States. Science of the Total Environment 806 (2022) 151318

Now, two new papers show how high the costs can be under some circumstances.

Eyal G. Frank compared the rate of infant mortality in counties across the U.S. where insectivorous bats had been severely reduced by whitenose syndrome to that in counties where bat populations were not affected. He found that “internal” infant mortality – defined as deaths not caused by accidents or homicides — rose, on average, 7.9%. An estimated additional 1,334 infants died. [A related finding not directly pertinent to this blog’s purpose: Frank notes that real-world use levels of insecticides have a detrimental impact on health, even when used within regulatory limits.]

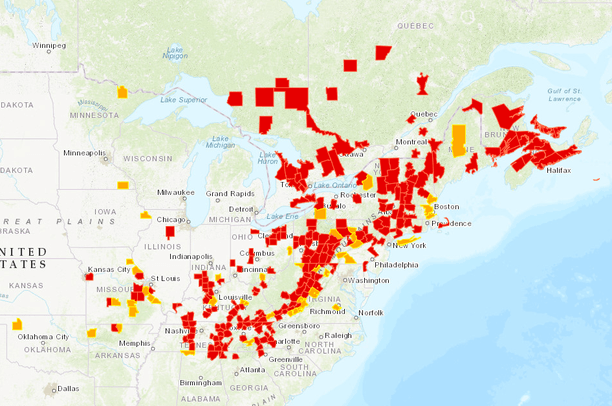

Whitenose syndrome (WNS) is caused by Pseudogymnoascus destructans, a fungus native to Europe. It was introduced to North America around the beginning of the 21st Century. It has spread quickly since its initial detection in 2006. By 2024, populations of 12 of ~ 50 insectivorous bat species in the US have been negatively affected. The fungus has caused an estimated decline of more than 90% in bat populations monitored in hibernating caves (Larson, Engst, and Noack 2024).

This population crash is devastating, especially where pest control is supplied by bats. Individual bats are voracious predators. But, for pest control to succeed, the total population must be high. .

Frank compiled information at the county level on:

- the spread of white nose syndrome to new counties;

- rates of pesticide application, presuming that higher rates reflected increased insect presence on crops; and

- infant mortality rates.

Larson, Engst, and Noack (2024) call Frank’s findings on infant mortality “shockingly large”. The increase in insecticide application rates was just 2.7 kg/km2. These findings show that technological substitutes for suppressed biological services can markedly and adversely affect human well-being.

Both Frank and Larson, Engst, and Noack emphasize the value in demonstrating that declines in biological diversity do have repercussions for human well-being. They call for more expansive and intensive monitoring of biodiversity trends, especially among non-charismatic taxa such as insects. Furthermore, there should be more multidisciplinary studies that integrate social, natural, and health datasets and research methods to distill information of policy relevance. The Science authors’ expectation is that quantifying these relationships will guide better decisions about conservation policies.

All the authors devote considerable attention to the difficulty in establishing these links because scientists cannot manipulate large-scale ecosystems to conduct experiments. They recommend taking advantage of natural experiments – such as tracking the spread of a newly introduced disease that kills large proportions of a taxon that provides demonstrated ecosystem services. Frank studied the loss of insectivorous bats. Larson, Engst, and Noack (2024) mention an earlier study of the collapse of amphibian populations in Central America caused by the fungal pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. One result in this case was an increase in the incidence of malaria.

Frank and Larson, Engst, and Noack clearly hope that this approach will promote stronger and more targetted biodiversity conservation policies and programs. I hope they are right! But did enough Americans hear about these results? I heard a report on “BBC America” radio. I searched and found a print report published by Vox – which connected me to Science. How do we expand media coverage of this type of information?

SOURCES

Frank, E.G. 2024. The economic impacts of ecosystem disruptions: Costs from substituting biological pest control. Science. 6 Sep 2024 Vol 385, Issue 6713 DOI: 10.1126/science.adg0344

The economic impacts of ecosystem disruptions: Costs from substituting biological pest control | ScienceThe econ impacts of ecosystem disruptions: Costs from substituting biological pest control | Science

Larson, A.E., Engist, D., Noack, F. 2024. The long shadow of Biodiversity loss: Technological substitutes are poor proxies for functioning ecosystems. Science 5 Sep 2024 Vol 385, Issue 6713 pp. 1042-1044 DOI: 10.1126/science.adq2373 The long shadow of BD loss | Science

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at https://treeimprovement.tennessee.edu/

or