Research scientists in the USFS Northern Region (Region 9) – Maine to Minnesota, south to West Virginia and Missouri – continue to be concerned about regeneration patterns of the forest and the future productivity of northern hardwood forests.

The most recent study of which I am aware is that by Stern et al. (2023) [full citation at the end of this blog]. They sought to determine how four species often dominant in the Northeast (or at least in New England) might cope with climate change. Those four species are red maple (Acer rubrum), sugar maple (Acer saccharum), American beech (Fagus grandifolia), and yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis). The study involved considerable effort: they examined tree ring data from 690 dominant and co-dominant trees on 45 plots at varying elevations across Vermont. The tree ring data allowed them to analyze each species’ response to several stressors over the 70-year period of 1945 to 2014.

In large part their findings agreed with those of studies carried out earlier, or at other locations. As expected, all four species grew robustly during the early decades, then plateaued – indicative of a maturing forest. All species responded positively to summer and winter moisture and negatively to higher summer temperatures. Stern et al. described the importance of moisture availability in non-growing seasons – i.e., winter – as more notable.

The American Northeast and adjacent areas in Canada have already experienced an unprecedented increase of precipitation over the last several decades. This pattern is expected to continue or even increase under climate change projections. However, Stern et al. say this development is not as promising for tree growth as it first appears. The first caveat is that winter snow will increasingly be replaced by rain. The authors discuss the importance of the insulation of trees’ roots provided by snow cover. They suggest that this insulation might be particularly necessary for sugar maple.

The second caveat is that precipitation is not expected to increase in the summer; it might even decrease. Their data indicate that summer rainfall – during both the current and preceding years – has a significant impact on tree growth rates.

Stern et al. also found that the rapid rise in winter minimum temperatures was associated with slower growth by sugar maple, beech, and yellow birch, as well as red maple at lower elevations. Still, temperature had less influence than moisture metrics.

Stern et al. discuss specific responses of each species to changes in temperatures, moisture availability, and pollutant deposition. Of course, pollutant levels are decreasing in New England due to implementation of provisions of the Clean Air Act of 1990.

They conclude that red maple will probably continue to outcompete the other species.

In their paper, Stern et al. fill in some missing pieces about forests’ adaptation to the changing climate. I am disappointed, however, that these authors did not discuss the role of biotic stressors, i.e., “pests”.

They do report that growth rates of American beech increased in recent years despite the prevalence of beech bark disease. They note that others’ studies have also found an increase in radial growth for mature beech trees in neighboring New Hampshire, where beech bark disease is also rampant.

For more specific information on pests, we can turn to Ducey at al. – also published in 2023. These authors expected American beech to dominate the Bartlett Experimental Forest (in New Hampshire) despite two considerations that we might expect to suppress this growth. First, 70-90% of beech trees were diseased by 1950. Second, managers have made considerable efforts to suppress beech.

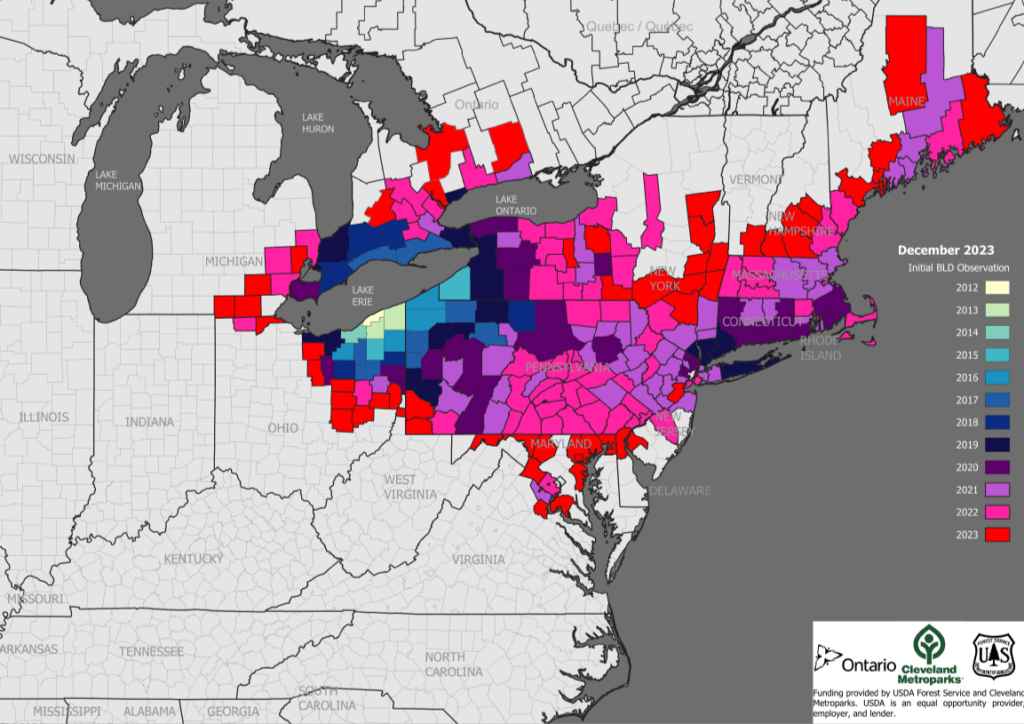

Stern et al. say specifically that their study design did not allow analysis of the impact of beech bark disease. I wonder at that decision since American beech is one of four species studied. More understandable, perhaps, is the absence of any mention of beech leaf disease. In 2014, the cutoff date for their growth analysis, beech leaf disease was known only in northeastern Ohio and perhaps a few counties in far western New York and Pennsylvania. Still, by the date of publication of their study, beech leaf disease was recognized as a serious disease established in southern New England.

Eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) and northern red oak (Quercus rubra) are described as common co-occurring dominant species in the plots analyzed by Stern et al. Although hemlock woolly adelgid has been killing trees in southern Vermont for years, Stern et al. did not discuss the possible impact of that pest on the forest’s regeneration trajectory. Nor did they assess the possible effects of oak wilt, which admittedly is farther away (in New York (& here) and in Ontario, Canada, west of Lake Erie).

In contrast, Ducey at al. (2023) did discuss link to blog 344 the probable impact of several non-native insects and diseases. In addition to beech bark disease, they addressed hemlock woolly adelgid, emerald ash borer, and beech leaf disease.

Non-native insects and pathogens are of increasing importance in our forests. To them, we can add overbrowsing by deer, proliferation of non-native plants, and spread of non-native earthworms. There is every reason to think the situation will only become more complex. I hope forest researchers will make a creative leap – incorporate the full range of factors affecting the future of US forests.

I understand that such a more integrated, holistic analysis might be beyond any individual scientist’s expertise or time, funding, and constraints of data availability and analysis. I hope, though, that teams of collaborators will compile an overview based on combining their research approaches. Such an overview would include human management actions, climate variables, established and looming pest infestations, etc. I hope, too, that these experts will extrapolate from their individual, site-specific findings to project region-wide effects.

Some studies have taken a more integrative approach. Reed, Bronson, et al. (2022) studied interactions of earthworm biomass and density with deer. Spicer et al. (2023) examined interactions of deer browsing and various vegetation management actions. Hoven et al. (2022) considered interactions of non-native shrubs, tree basal area, and forest moisture regimes.

See also my previous blogs on studies of regeneration in New Hampshire, North Carolina, National parks in the East, Allegheny Plateau and Ohio, and the impact of deer.

SOURCE

Stern, R.L., P.G. Schaberg, S.A. Rayback, C.F. Hansen, P.F. Murakami, G.J. Hawley. 2023. Growth trends and environmental drivers of major tree species of the northern hardwood forest of eastern North America. J. For. Res. (2023) 34:37–50 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-022-01553-7

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at https://treeimprovement.tennessee.edu/

or