I learned at the beginning of August that Canadian scientists have discovered a new pathogen causing wilt disease on American elms (Ulmus americana). The pathogen is Plenodomus tracheiphilus, which is known primarily for causing serious disease in citrus.

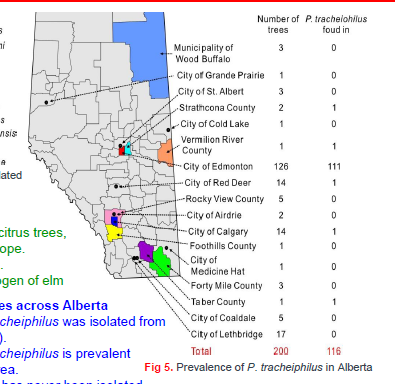

P. tracheiphilus is described as common on Alberta’s elm trees, especially in the Edmonton area. It was found on 116 of 200 trees which were sampled – see map. The wilting had previously been blamed on Dothiorella ulmi. I have been unable to find a source for the geographic origin of Dothiorella ulmi; perhaps it is native to North America. It is reported to be present at least from Alberta to Texas. (Presumably if Plenodomus tracheiphilus were in Texas it would have caused obvious symptoms on that state’s citrus crops.)

I am unaware of any North American forest pathologists studying whether this pathogen is also established in the United States, or its possible effects. The discovery in Alberta is the first time this organisms has been associated with disease on elms; I have asked European and North American forest pathologists whether they are looking into possible disease on any of the European or North American elm species. So far, no one reports that s/he has been.

In the meantime, the California Department of Food and Agriculture has begun the process of assigning Plenodomus tracheiphilus the highest pest risk designation for the state. CDFA is worried primarily about damage to the state’s $2.2 billion citrus industry. CDFA is seeking comments on its proposed action; go here .

CDFA points out that despite awareness of the disease on economically important citrus since at least 1900 and efforts by phytosanitary agencies, it has spread to most citrus-growing countries around the Mediterranean and Black seas and parts of the Middle East. The primary mode of spread is movement of infected plant material, e.g., rootstocks, grafted plants, scions, budwood, and even fruit peduncles and leaves. Transmission is possible from latently infected, asymptomatic material. Once established at a site, the conidia produced on diseased plant parts can be spread over relatively short distances by rain-splash, overhead irrigation, water surface flow, or wind-driven rain. Transport by birds and insects is also suspected. The pathogen can survive on pruned material or in soil containing infected plant debris for up to four month.

The report from Canada does not speculate on how a disease associated with plants in a Mediterranean climate was transported to Alberta, which has a cold continental climate. Nor is there any information on the possible presence of the disease on elms in warmer parts of Canada.

U.S. elms appear to be at high risk because phytosanitary restrictions leave dangerous gaps.

First, under the Not Authorized for Importation Pending Pest Risk assessment (NAPPRA) program, USDA APHIS has prohibited importation of plants in the Ulmus genus from all countries except Canada. Second, importation of cut greenery is allowed from all countries – and the CDFA analysis indicates that the pathogen can be transported on leaves. Third, it appears to me that it is probable that this pathogen survives on plants in additional taxa.

See this profile for a description of other threats to North American elms.

SOURCES

Poster prepared by Alberta Plant Health Lab, Alberta Agriculture & Irrigation, and Society to Prevent Dutch Elm Disease https://www.alberta.ca/system/files/agi-plenodomus-poster.pdf

Yang, Y., H. Fu, K. Zahr, S. Xue, J. Calpas, K. Demilliano, et al. 2024. Plenodomus tracheiphilus, but not Dothiorella ulmi, causes wilt disease on elm trees in Alberta, Canada. European Journal of Plant Pathology 169(2):409-420. Last accessed August 1, 2024, from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10658-024-02836-x

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at https://treeimprovement.tennessee.edu/

or