Scientists in New Zealand have recently completed a study of the probable impact of myrtle rust – caused by Austropuccinia psidii – on plants in the plant family Myrtaceae. McCarthy et al. say their results should guide management actions to protect not only the unique flora of those islands but also on Australia and Hawai`i – other places where key dominant tree species are susceptible to myrtle rust. The disease attacks young tissue; susceptible Myrtaceae become unable to recruit new individuals or to recover from disturbance. Severe cases can result in tree death & localized extinctions

[I note that myrtle rust is not the only threat to the native trees of these biologically unique island systems. New Zealand’s largest tree, kauri (Agathis australis), is threatened by kauri dieback (caused by Phytophthora agathidicida). On Hawai`i, while the most widespread tree, ‘ōhi‘a (Metrosideros polymorpha) is somewhat vulnerable to the strain of rust introduced to the Islands, the greater threat is from a different group of fungi, Ceratocystis lukuohia and C. huliohia, collectively known as rapid ‘ōhi‘a death. On Australia, hundreds of endemic species on the western side of the continent are being killed by Phytophthora dieback, caused by Phytophthora cinnamomi. [I note the proliferation of tree-kiling pathogens; I will blog more about this in the near future.]

Myrtle rust arrived in New Zealand in 2017, probably blown on the wind from Australia (where it was detected in 2010). In New Zealand, myrtle rust infects at least 12 of 18 native tree, shrub, and vine species in the Myrtaceae plant family. Several of these species are important in the structure and succession of native ecosystems. They also have enormous cultural significance.

McCarthy et al. note that species differ in their contribution to forest structure and function. They sought to determine where loss of vulnerable species might have the greatest impact on community functionality. They also explored whether compensatory infilling by co-occurring, non-vulnerable species in the Myrtaceae would reduce the community’s vulnerability. Even when co-occurring Myrtaceae are relatively immune to the pathogen, only some of them – the fast-growing species – are likely to fill the gaps. They might lack the functional attributes of the decimated species.

To identify areas at greatest risk, McCarthy et al. took advantage of a nationwide vegetation plot dataset that covers all the country’s native forests and shrublands. The plot data enabled McCarthy et al. to determine which plant species not vulnerable to the rust are present and so are likely to replace the rust host species as they are killed.

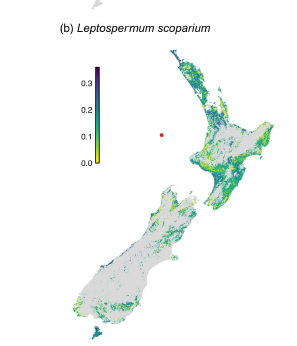

McCarthy et al. concluded that forests and shrublands containing Kunzea ericoides and Leptospermum scoparium are highly vulnerable to their loss. Ecosystems with these species are found predominantly in central and southeastern North Island, northeastern South Island, and Stewart Island. While compensatory infilling by other species in the Myrtaceae would moderate the impact of the loss of vulnerable species, if these co-occurring species were unable to respond for various reasons, such as also being infected by the rust pathogen, community vulnerability almost always increased. In these cases the infilling species would probably have different functional attributes. In many areas the species most likely to replace the rust-killed native species would be non-native shrubs. Consequently, early successional woody plant communities, where K. ericoides and L. scoparium dominate, are at most risk.

Because the risk of A. psidii infection is lower in cooler montane and southern coastal areas, parts of inland Fiordland, the northwestern South Island and the west coast of the North Island might be less vulnerable.

Austropuccinia psidii has been spreading in Myrtaceae-dominated forests of the Southern Hemisphere since the beginning of the 21st Century. It was detected in Hawai`i in 2005; in Australia in 2010; in New Caledonia in 2013, and finally in New Zealand in 2017. Within 12 months of its first detection in the northern part of the North Island it had spread to the northern regions of the South Island.

Specific types of Threat

Succession

The ecosystem process most at risk to loss of Myrtaceae species to A. psidii is succession. About 10% of once-forested areas of New Zealand are in successional shrublands, mostly dominated by Kunzea ericoides and Leptospermum scoparium. Both species are wind dispersed, grow quickly, are resistant to browsing by introduced deer, and are favored by disturbance, especially fire. Both are tolerant of exposure and have a wide edaphic range (including geothermal soils). Still, K. ericoides prefers drier, warmer sites while L. scoparium tolerates saturated soils, frost hollows and subalpine settings.

Loss of these two species would result in a considerable change in stand-level functional composition across a wide variety of locations. Their extensive ranges mean that it would be difficult for other species – even if functionally equivalent – to expand sufficiently quickly. Second, non-native species are common in these communities. All of these invaders – Ulex europaeus, Cytisus scoparius and species of Acacia, Hakea and Erica – promote fire. Some are nitrogen fixers. While they can facilitate succession, the resulting native forest will differ from that formed via Leptospermeae succession. Furthermore, compensatory infilling by the invasive species might also reduce carbon sequestration. Successional forests dominated by K. ericoides are significant carbon sinks owing to the tree’s size (up to 25 m under favorable conditions), high wood density, and long lifespan (up to ~150 years). In contrast, shrublands dominated by at least one of the non-native species, U. europaeus, are significant carbon sources.

Northern and central regions of the North Island and the northeastern and interior parts of the South Island are most vulnerable to the loss of these species since these successional shrub communities are widespread and the area’s climate is highly suitable for A. psidii infection. The southern regions of the South Island, including Stewart Island, are somewhat protected by the cooler climate.

Fortunately, neither Kunzea ericoides nor Leptospermum scoparium has yet been infected in nature. Laboratory trials indicate that some families of K. ericoides are resistant. Vulnerability also varies among types of tissue – i.e., leaf, stem, seed capsule.

Forest biomass

Although from the overall community perspective loss of species in the Metrosidereae would have a lower impact than loss of those in the Leptospermeae, there would be significant changes associated with loss of Metrosideros umbellata. This species can grow quite large (dbh often > 2 m; heights up to 20 m). That size and its exceptionally dense wood means that M. umbellata stores high amounts of carbon. Also, its slow decomposition provides habitat for decomposers. Lessening the potential impact of loss of this species are two facts: its litter nutrient concentrations and decomposition rates do not differ from dominant co-occurring trees; and, most important, it grows primarily in the south, where weather conditions are less suitable for A. psidii infection. One note of caution: if A. psidii proves able to spread into these regions, not only M. umbellata but also susceptible co-occurring Myrtaceae species are likely to be damaged by the pathogen.

Highly specific habitats

McCarthy et al. note that their study might underestimate the impact of loss of species with unique traits that occupy specialized habitats. They focus on the climber Metrosideros excelsa. This is an important successional species that helps restore ecosystems following fire, landslides, or volcanic eruptions. The species’ tough and nutrient poor leaves promote later successional species by forming a humus layer and altering the microenvironment beneath the plant. Its litter has high concentrations of phenolics and decomposes more slowly than any co-occurring tree species. [They say its role is analogous to that of M. polymorpha in primary successions on lava flows in Hawai`i.] M. excelsa dominates succession on many small offshore volcanic islands, rocky coastal headlands and cliffs.

Another example is Lophomyrtus bullata, a small tree that is patchily distributed primarily in forest margins and streamside vegetation. This is the native species most affected by A. psidii; the pathogen is likely to cause its localized extinction. McCarthy et al. call for assessment of ex situ conservation strategies for this species.

Each of these species is represented in only seven of the plots used in the analysis, so community vulnerability to their loss might be underestimated.

Another habitat specialist, Syzygium maire, is found mostly in lowland forests, usually on saturated soils. It currently occupies only a fraction of its natural range due to deforestation and land drainage. Evaluating the impact of loss of S. maire is complicated by its poor representation in the database (only six plots), and the fact that many of the co-occurring species are also Myrtaceae.

Lack of data similarly prevents detailed assessment of the impacts from possible loss of other species, including M. parkinsonii, M. perforata and L. obcordata. McCarthy et al. say only that their disappearance will “take the community even further from its original state”.

McCarthy et al. warn that the risk could increase if more virulent strains of A. psidii were introduced or evolved through sexual recombination of the current pandemic strain. Other scientists have discovered strong evidence that the many strains of A. psidii attack different host species (see Costa da Silva et al. 2014).

McCarthy et al. note that other factors are also important in determining the impact of loss of a plant species. Especially significant is the host plant species’ association with other species. They say these relationships are poorly understood. One example is that only four Myrtaceae species produce fleshy fruits. Loss or decline of these four species might severely affect populations of native birds, many of which are endemic. Many invertebrates – also highly endemic — are dependent on nectar from other plants in the family.

In their conclusion, McCarthy et al. note that A. psidii has been introduced relatively recently so there is still time to reduce the disease’s potential consequences. They suggest such management interventions as identifying and planting resistant genotypes and applying chemical controls to protect important individual specimens. They hope their work will guide prioritization of both species and spatial locations. They believe such efforts have substantial potential to reduce myrtle rust’s overall functional impact to New Zealand’s unique ecosystems.

SOURCES

Costa da Silva, A; P.M. Teixeira de Andrade, A. Couto Alfenas, R. Neves Graca, P. Cannon, R. Hauff, D. Cristiano Ferreira, and S. Mori. 2014. Virulence and Impact of Brazilian Strains of Puccinia psidii on Hawaiian Ohia (Metrosideros polymorpha). Pacific Science 68(1):47-56. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.2984/68.1.4

McCarthy, J.K., S.J. Richardson, I. Jo, S.K. Wiser, T.A. Easdale, J.D. Shepherd, P.J. Bellingham. 2024. A Functional Assessment of Community Vulnerability to the Loss of Myrtaceae From Myrtle Rust. Diversity & Distributions, 2024; https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.13928

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at https://treeimprovement.tennessee.edu/

or